I’ve been framing trust the wrong way.

For months I’ve been asking the wrong question about AI-generated code. “Do I understand what this does?” That’s rarely how trust operates in complex systems. Maybe it never was.

The epistemological shift required to trust AI-generated code mirrors transitions we’ve already been through: compiler adoption, cockpit automation, statistical process control. Every time, humans learned to trust procedural verification over cognitive comprehension. The developers who struggled? They kept asking “Do I understand this?” The ones who adapted? They asked “Have I verified this adequately?”

The Trust Paradox in Real Numbers

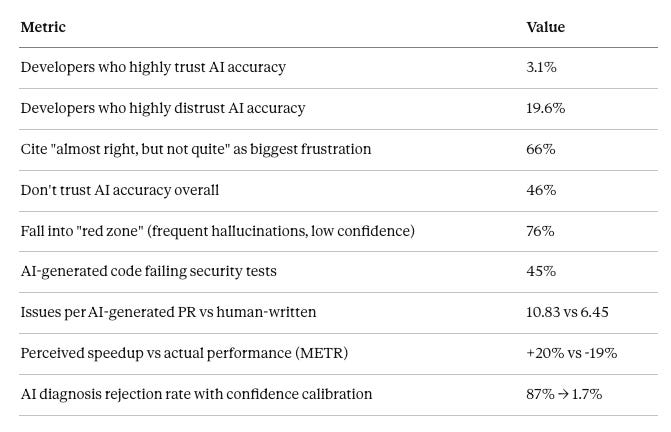

The Stack Overflow 2025 Developer Survey dropped some fascinating data. Only 3.1% of developers highly trust AI output accuracy. Yet 51% use AI tools daily. That gap doesn’t close through belief. It closes through process.

Among all developers surveyed, 46% distrust AI accuracy compared to just 33% who trust it. Experience correlates with skepticism: developers with 10+ years show the lowest “highly trust” rate (2.5%) and highest “highly distrust” rate (20.7%). We’re not talking about Luddites. These are people who’ve been burned enough to know better.

But here’s the thing that matters: 66% cite “AI solutions that are almost right, but not quite” as their biggest frustration. Not wrong. Almost right. That near-miss problem makes cognitive verification exhausting. You can’t skim AI output. You have to actually read it, and reading code is harder than writing it.

One highly-upvoted comment on Hacker News captured this tension: “Famously, ‘it’s easier to write code than to read it.’ That goes for humans. So why did we automate the easy part and moved the effort over to the hard part?”

The Vibe Coding Backlash

The Qodo State of AI Code Quality Report 2025 quantified what many of us feel: 76% of developers fall into what they call the “red zone”—frequent hallucinations, low confidence in generated code. Meanwhile “vibe coding” has emerged as a lightning rod. Only 15% of developers actively use vibe coding professionally. 72% reject it entirely.

One comment from r/programming resonated across developer communities: “I just wish people would stop pinging me on PRs they obviously haven’t even read themselves, expecting me to review 1000 lines of completely new vibe-coded feature that isn’t even passing CI.”

Another developer compared vibe coding to an electrician who “just threw a bunch of cables through your walls and hoped it all worked out—things might function initially, but hidden flaws lurk behind the walls.”

Here’s what I take from this backlash. Developers aren’t rejecting AI assistance. They’re demanding verification infrastructure. The emerging consensus points toward spec-driven development (write requirements first), test-first verification (AI generates tests alongside code), and incremental acceptance (small, verifiable chunks rather than wholesale generation).

The Compiler Parallel Holds Up

Vivek Haldar’s February 2025 essay “When Compilers Were the ‘AI’ That Scared Programmers” provides the strongest historical parallel. In the 1950s, assembly programmers exhibited the same resistance patterns we’re seeing now.

“Many assembly programmers were accustomed to having intimate control over memory and CPU instructions. Surrendering this control to a compiler felt risky. There was a sentiment of, ‘if I don’t code it down to the metal, how can I trust what’s happening?’”

Three resistance arguments from the compiler era map to AI resistance today:

The efficiency argument. Compiled code couldn’t match hand-tuned assembly. Proven false once optimizing compilers matured.

The control argument. Loss of direct understanding meant loss of reliability. Resolved through trust in process.

The prestige argument. Easier programming might “reduce the prestige or necessity of the seasoned programmer.” The reverse happened. Demand exploded as accessible tools enabled new applications.

Grace Hopper faced this directly. Management and colleagues initially thought automatic programming was crazy, fearing it would make programmers obsolete. The resolution came through performance proof (IBM’s Fortran team delivered an optimizing compiler that matched assembly speed) and procedural transparency (compilers began providing diagnostic output that actually improved understanding).

Haldar’s conclusion: “The debate playing out today about what it means to be a programmer when LLMs can churn out large amounts of working code is of exactly the same shape. Let’s learn from it and not make the same mistakes.”

But the Analogy Has Limits

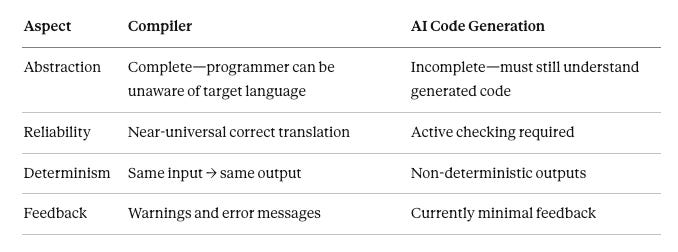

Microsoft Research’s Advait Sarkar challenges an easy mapping. His PPIG paper identifies crucial differences between compilers and AI code generation:

Sarkar notes: “Unlike with compilers, a programmer using AI assistance must still have a working knowledge of the target language, they must actively check the output for correctness, and they get very little feedback for improving their ‘source’ code.” This is “fuzzy abstraction matching”—the AI approximates intent rather than translating deterministically.

Here’s why this complication actually strengthens the procedural trust argument. Because AI is less deterministic than compilers, cognitive comprehension becomes even less viable as a primary trust strategy. Understanding still matters for debugging and oversight, but verification infrastructure becomes the load-bearing mechanism. You can’t understand your way to trust with a non-deterministic system. You have to verify your way there, with comprehension serving as a secondary check rather than the foundation.

Aviation Figured This Out Already

The transition from “pilot understands all systems” to “pilot trusts instrumentation” took roughly 18 years (1982-2000). The Flight Safety Foundation documented how automation changed a pilot’s role to that of a systems manager whose primary task is to monitor displays and detect deviations. A classic vigilance task.

The automation problems mirror AI coding concerns precisely. Automation bias: pilots using automation as a substitute for information gathering. Over trust: “Pilots start trusting the systems because of the fantastic job it does, and start no longer worry about the integrity of the systems.” Skills atrophy: pilots losing manual flying skills.

The NTSB found that while pilots preferred the glass cockpit design and believed it improved safety, they found learning to use the displays and maintaining their proficiency to be more difficult.

The resolution is instructive. Airbus now explicitly tells pilots to keep the autopilot engaged during turbulence rather than intervening manually. Data showed that in 25% of temporary overspeed events, pilots who disconnected the autopilot made manual inputs that worsened the situation.

Procedural trust proved more effective than relying solely on cognitive understanding.

Medical Diagnostics Show the Mechanism

A 2025 study on AI-assisted cardiac diagnostics found something striking. When physicians reviewed AI diagnoses, they rejected the system’s conclusions 87% of the time. But when the AI began reporting its own confidence level, rejection fell to 33%. When the AI was highly confident, doctors accepted findings in almost every case. The override rate dropped to just 1.7%.

Doctors didn’t need to understand the algorithm’s internals. They needed confidence calibration—the AI communicating its certainty level. Trust became a function of procedural signals (confidence scores, explanations of reasoning) rather than cognitive penetration of the model.

Algorithm aversion research shows a consistent preference for humans’ opinions over algorithms, even when the algorithms are known to be superior. But this preference diminishes when humans can choose their AI tools. Trust increases through procedural autonomy. Nobody likes being forced to use a tool. Give people the choice and watch trust grow.

Manufacturing’s Statistical Process Control Is Pure Procedural Trust

Walter Shewhart’s 1924 development of control charts at Bell Labs established the paradigm that still governs quality management. Workers didn’t need to understand why variation occurred, just whether it was within control limits. Shewhart distinguished “common cause” variation (inherent to process) from “special cause” variation (external factors). The procedural response: trust the chart, not your intuition.

Statistical process control became the foundation for quality in everything from munitions manufacturing to Six Sigma. The core shift was from detection (inspecting finished products) to prevention (monitoring processes that catch problems before they manifest).

This maps directly to AI coding verification. Catch problems through tests and invariants before production, rather than trying to comprehend every line.

The Philosophy Actually Helps Here

Philosopher C. Thi Nguyen’s framework in “Trust as an Unquestioning Attitude” provides the most precise conceptual foundation. He defines trust not as mere reliance but as reliance with suspended deliberation: “What it is to trust, in this sense, is not simply to rely on something, but to rely on it unquestioningly. It is to rely on a resource while suspending deliberation over its reliability.”

Nguyen argues we can trust non-agents—ropes, tools, the ground: “We can be betrayed by our smartphones in the same way that we can be betrayed by our memory.” When we trust things, we grant them a degree of cognitive intimacy which approaches that of our own internal cognitive faculties.

This maps directly to AI tools. Cognitive trust (understanding why it works) isn’t feasible for complex systems. But Nguyen’s “unquestioning attitude” can be earned through procedural mechanisms: consistent behavior, passed tests, observable failures caught and corrected. We develop trust in AI tools the way we develop trust in any tool—through repeated successful use within verification constraints.

Michael Polanyi’s tacit knowledge concept adds another layer. “We can know more than we can tell.” Much expertise cannot be articulated into explicit rules. Some research estimates 70-80% of software organization knowledge is tacit (undocumented, experience-based), though precise measurement varies by context. AI tools may embody tacit patterns without being able to explain them. Just as we trust human experts with tacit knowledge, we can trust AI tools verified through outcomes rather than explanations.

Zero Trust Architecture Offers the Blueprint

The “never trust, always verify” principle from zero trust architecture provides a procedural framework. NIST SP 800-207 defines it as a security framework requiring all users to be authenticated, authorized, and continuously validated before being granted access. No implicit trust based on network location. Continuous verification of every request.

This eliminates trust assumptions and replaces them with verification. A purely procedural approach. Applied to AI coding: every AI-generated line of code passes through verification gates (tests, static analysis, security scanning) regardless of source. Trust resides in the verification infrastructure, not in understanding the generator.

Extended Cognition Reframes Everything

Andy Clark and David Chalmers’ Extended Mind thesis argues cognitive processes extend beyond the brain. Their “Parity Principle”: If, as we confront some task, a part of the world functions as a process which, were it done in the head, we would have no hesitation in recognizing as part of the cognitive process, then that part of the world is part of the cognitive process.

Clark’s 2025 paper in Nature Communications extends this to AI: “We humans are and always have been ‘extended minds’—hybrid thinking systems defined (and constantly re-defined) across a rich mosaic of resources only some of which are housed in the biological brain.”

AI coding tools can become genuine extensions of cognitive systems when properly integrated—trusted through the same mechanisms we trust our own memory (which also fails, also requires verification through external notes and checks).

The Practical Verification Stack Is Crystallizing

Best practices are emerging that reflect procedural trust architecture:

Guardrails at generation. Codacy’s system integrates directly with AI coding assistants to enforce coding standards and prevent non-compliant code from being generated in the first place. Snyk recommends making access to AI coding assistants contingent on the local security setup. Constraint replaces comprehension.

Test coverage as trust proxy. Addy Osmani recommends >70% test coverage as a minimum gate for AI-generated code. “The developers who succeed with AI at high velocity aren’t the ones who blindly trust it; they’re the ones who’ve built verification systems that catch issues before they reach production.”

Observability as continuous verification. OpenTelemetry’s GenAI SIG is developing standards for tracking agent actions, reasoning traces, tool calls, and performance metrics. The infrastructure for procedural trust is being built.

Formal verification for AI output. The “Genefication” approach uses generative AI to draft code or specifications, followed by applying formal verification to rigorously ensure that the design satisfies critical safety and correctness properties. AI generates; formal methods verify. Pure procedural trust.

The Identity Crisis Is Real

Luca Rossi’s January 2026 essay “Finding Yourself in the AI Era” captures the identity dimension. He distinguishes puzzle-solvers (who find coding intellectually stimulating; AI removes the satisfying parts) from problem-solvers (who care about shipping; complexity gets in the way).

For puzzle-solvers, AI assistance feels like having someone else solve your crossword puzzles for you.

Rossi notes common comfort-driven behaviors: “I only use LLMs as autocomplete so I can check every single line of code”; “It takes more time to review LLM code than to write it myself”; “If I make AI write it, my skills will atrophy.”

These may be rationalizations. “You should keep your antennas up and intercept when your behavior is guided by your own comfort, as opposed to what is best for the team/product/business.”

The MIT Technology Review captured developer Luciano Nooijen’s experience: “I was feeling so stupid because things that used to be instinct became manual, sometimes even cumbersome... Just as athletes still perform basic drills, the only way to maintain an instinct for coding is to regularly practice the grunt work.”

Skills atrophy is real. A genuine cost of procedural trust that requires deliberate counter-measures.

The METR study found that experienced developers believed AI made them 20% faster while objective tests showed they were actually 19% slower. The perception gap reveals how much identity and self-image are at stake.

The Craft Identity Question

Stack Overflow’s editorial team posed the anxiety question directly: “Are you a real coder, or are you using AI?” The answer they propose—”Yes”—doesn’t resolve the tension. AI coding tools create “developers who don’t understand the context behind the code they’ve written or how to debug it.”

The difference between “I trust this” and “I understand this” is the gap where craft identity lives.

One developer quoted in the Enterprise Spectator deactivated Copilot after two years: “The reason is very simple: it dumbs me down. I’m forgetting how to write basic things, and using it at scale in a large codebase also introduces so many subtle bugs which even I can’t usually spot directly. Call me old fashioned, but I believe in the power of writing, and thinking through, all of my code, by hand, line by line.”

That loss is real. Loss of a relationship to the craft that some developers built their identities around.

Colton Voege addressed the social pressure: “I wouldn’t be surprised to learn AI helps many engineers do certain tasks 20–50% faster, but the nature of software bottlenecks means this doesn’t translate to a 20% productivity increase—and certainly not a 10× increase.” His permission: “It’s okay to sacrifice some productivity to make work enjoyable.”

What the Timeline Looks Like

Based on historical evidence, trust transitions follow a pattern: initial resistance (2-5 years), performance proof (3-10 years), procedural codification (5-15 years), normalized trust (10-20+ years).

Compiler adoption took roughly 20 years (1955-1975). Glass cockpit adoption took roughly 18 years (1982-2000). AI coding tools launched 2022—we’re in year 3-4 of what may be a 15-20 year transition.

The trust probably won’t come from AI tools becoming cognitively transparent, at least not in the short term. It will come from verification infrastructure becoming reliable, from procedural safeguards becoming standard, and from a new generation of developers who never knew any other way.

The Numbers to Remember

Frameworks Worth Keeping

Trust Debt. Every time you accept AI output without verification, you borrow against future understanding. Someone eventually must “pay” by deeply reviewing that code.

The Junior Developer Model. Treat AI as a junior teammate—fast but unreliable, needs supervision, never the final word. (maybe junior → journeyman at this point)

Nguyen’s Unquestioning Attitude. Trust emerges through consistent, reliable behavior over time—the climbing rope that has held many times, the test suite that continues to pass.

Zero Trust Applied. “Never trust, always verify”—continuous checking through tests, invariants, and observable failures creates trust without cognitive penetration.

Extended Cognition. AI tools become extensions of our cognitive systems when properly integrated—trusted through the same mechanisms we trust our own memory.

The Bottom Line

There’s growing evidence that supports shifting from comprehension-based to verification-based trust. You don’t need to understand every line of AI-generated code. You need verification systems that catch problems before they reach production.

The psychological transition remains difficult. Developer craft identity is built on understanding code; procedural trust asks developers to accept that understanding everything is no longer possible or necessary. That loss is real. But the same was true for assembly programmers, pilots, and quality inspectors.

The emerging infrastructure—guardrails, observability, confidence calibration, test coverage gates, chain-of-thought monitoring—provides the verification architecture that makes procedural trust rational. The question has shifted.

Not “Do I understand this code?” but “Have I verified this code adequately?”

That’s a procedural rather than cognitive form of trust. And it’s how we’ll learn to work with AI that writes code we can’t fully comprehend.

I’m Bob Matsuoka, writing about agentic coding and AI-powered development at HyperDev. For more on how trust actually works with AI tools, read my analysis of non-deterministic debugging challenges or my deep dive into multi-agent orchestration.

Verification and comprehension are not mutually exclusive. You might be right that instead of starting with comprehension it may make sense to *start with* verification. And then whether to proceed to comprehension is a judgment call based on the cost of failure, our understanding of the tool's strengths and weaknesses as well as past experience.

Most of the examples provided don't involve non-determinism. I think it's the non-determinism that often disturbs our intuition, especially in those cases where it is incidental, not essential. I like some creativity when writing an essay, but not when counting. And, with a compiler, if we were concerned enough, we could understand how it works and why it works a certain way.

I do think that, if we are to leverage the power of AI-generated code without blind trust, we may need to think probabilistically in cases that make us uncomfortable.

A reader has kindly pointed out there are a few incorrect links in the article. I apologize for that, will correct them today.