The Quiet Math Behind $500 Billion: How Many Engineers Must AI Replace?

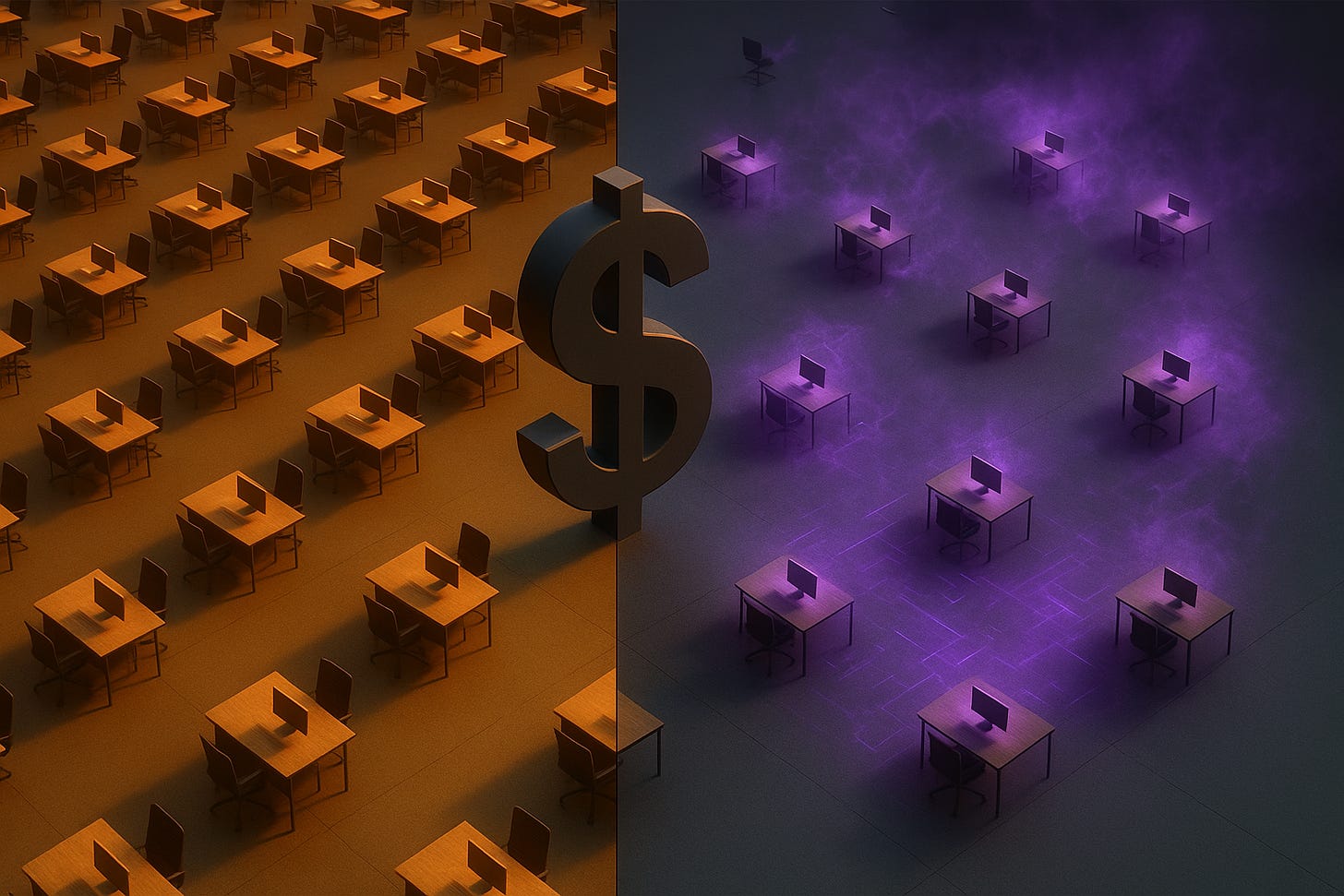

Rumblings of the next Industrial Revolution - The AI Revolution?

OpenAI’s Sora Android case study is interesting on a few levels. What they achieved—four engineers, 28 days, shipping #1 on Google Play—validates a lot of what I’ve been writing about: AI-assisted development genuinely can compress timelines when conditions are right. What it took to get there—5 billion tokens, unlimited internal API access, a complete iOS codebase to translate from—tells a more complicated story about reproducibility.

But there’s an even more interesting angle here. The economics.

OpenAI’s $500 billion valuation sits at 167x revenue. Traditional SaaS companies trade at 5-10x. Investors aren’t paying that for chatbot subscriptions. They’re pricing in workforce transformation at a scale we haven’t seen since factories replaced craftsmen.

The question nobody wants to ask directly: How many junior engineers need to lose their jobs to justify that number?

What follows is an economic thought experiment. The math is directional, not precise. Real-world outcomes depend on variables nobody can predict—adoption curves, competitive dynamics, regulatory responses, and whether the technology actually delivers on its promises. But running the numbers reveals what investors are implicitly betting on.

The Sora Android Case Study—Real Costs Revealed

OpenAI published what looked like a victory lap last week. Four engineers built Sora for Android in 28 days using 5 billion tokens. The achievement seemed impressive until you run the actual numbers.

Those 5 billion tokens? At rack API rates—what external developers actually pay—the cost would run $25,000 to $75,000 depending on model selection and caching strategy. OpenAI’s engineers had unlimited internal credits, likely at marginal cost approaching zero. Few external teams could match this cost profile without similar institutional access.

But here’s what should deeply concern junior developers: even at $75,000 in token spend, the project cost roughly half what traditional development would have required.

A typical iOS-to-Android port takes 3-6 months with 2-4 engineers. Call it 400 engineer-days at conservative estimates. At fully loaded costs of roughly $600/day—calculated from $130,000 annual cost divided by ~217 working days—that’s $240,000 in traditional labor costs.

The AI-assisted approach: 112 engineer-days of human work plus $50,000 in tokens (splitting the difference on estimates). Total cost: roughly $117,000.

The estimated savings: $123,000 per project—assuming clean handoff, no major regressions, and minimal integration complexity. Real-world projects involve QA cycles, organizational dynamics, and unexpected technical debt that could eat into these margins fast. The 51% cost reduction represents a best-case scenario, not a guaranteed outcome.

The Fully Loaded Engineer Math

Let’s get specific about what a junior engineer actually costs an employer.

ZipRecruiter puts average junior developer salary at $94,542. PayScale says $71,196. Glassdoor lands at $130,241. The spread reflects geography—San Francisco juniors cost more than Austin juniors—and methodology differences. Let’s use $90,000 as a reasonable baseline for this analysis.

But salary isn’t cost. The Bureau of Labor Statistics June 2025 data shows total compensation runs 1.25x to 1.4x base salary when you add:

Employer FICA (7.65%)

Health insurance ($7,500-$11,000/year)

401(k) match (3-6%)

Equipment and software licenses

Office space ($3,000-$14,000/year per employee)

Management overhead

HR and administrative costs ($2,524/year per employee)

A $90,000 junior developer actually costs $120,000-$135,000 per year fully loaded. I’m using $130,000 as a working number for US-based juniors—roughly the midpoint of that range.

Globally, the math shifts. A junior developer in Poland or India might cost $40,000-$60,000 fully loaded. The worldwide average probably lands around $75,000 when you weight by population distribution—though that’s a rough estimate given how wildly regional costs vary.

OpenAI’s Valuation Requires What, Exactly?

OpenAI raised at $500 billion. They’re generating roughly $12-13 billion in annualized revenue. That’s where the 167x revenue multiple comes from—versus normal SaaS multiples of 5-10x.

Even aggressive SaaS growth companies rarely sustain 15-20x multiples. Microsoft trades at 12x revenue. Salesforce at 8x. The $500 billion number implies OpenAI needs to grow revenue to $50 billion just to reach a 10x multiple—which would still be aggressive for a company burning $26 billion annually.

Gap to fill: approximately $38 billion in additional annual revenue.

Where does that come from?

(A) Dramatically more subscriptions at current pricing.

(B) Enterprise deals at massive scale.

(C) Capturing value from workforce displacement.

Let’s run Option C—the scenario nobody likes to discuss. This isn’t the only path to justifying the valuation, but it’s the one most directly tied to productivity claims.

The Displacement Math

If OpenAI’s thesis is “we help companies do more with fewer engineers,” the revenue opportunity is workforce cost capture.

Scenario: AI displaces 50% of a junior engineer’s output.

This is a modeling assumption, not a prediction. Actual displacement could be higher, lower, or distributed unevenly across different types of work.

A company saves $65,000/year per junior engineer (half of $130,000 fully loaded cost). If OpenAI captures 30% of that value through subscriptions and API usage—a value-capture rate comparable to enterprise software—that’s $19,500 per displaced engineer-equivalent annually.

To generate $38 billion in additional revenue from displacement economics alone:

$38,000,000,000 ÷ $19,500 = 1.95 million engineer-equivalents

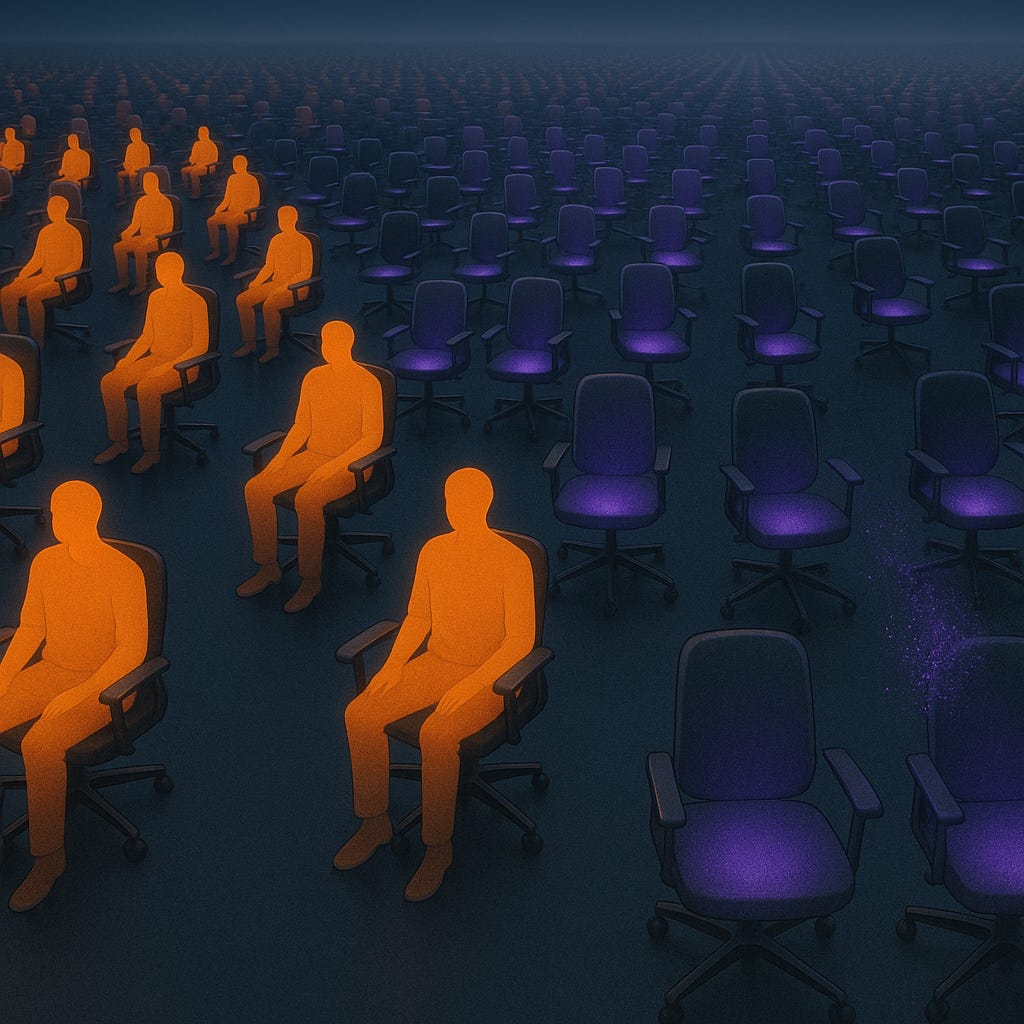

There are roughly 36.5 million professional developers globally, with about 11 million at junior/entry level (roughly 30% of the professional population). Displacing 1.95 million represents 17.7% of all junior developers worldwide.

One in six junior developers. That’s what the math implies—not as prediction, but as the scale required to justify current investment levels through workforce economics alone.

And that’s just engineers.

Broaden the thesis to knowledge workers generally—legal assistants, financial analysts, marketing coordinators, technical writers—and the numbers get worse. Knowledge workers outside software average lower fully loaded costs, maybe $75,000 globally versus $130,000 for US junior engineers. Lower cost per worker means you need to displace more of them to capture the same value.

Run the same math at $75,000 fully loaded:

$38,000,000,000 ÷ ($75,000 × 0.5 × 0.3) = 3.38 million knowledge workers

The investment thesis doesn’t require choosing between engineers and other knowledge workers. It likely requires both. OpenAI’s tools aren’t limited to code generation—they’re positioned for document drafting, analysis, research, communication. Every category of cognitive work that can be partially automated becomes part of the addressable displacement market.

The Per-Project Economics Tell a Harder Story

Return to the Sora example. Traditional approach: $240,000. AI-assisted: $117,000. Estimated savings: $123,000.

Those cost savings primarily reflect reduced staffing requirements. Compress 400 engineer-days into 112 and headcount follows.

The traditional 400 engineer-days required approximately 2-3 FTE engineers over 4-6 months. The AI-assisted approach used 4 engineers for one month. The difference: 1-2 engineer-years worth of work compressed or eliminated.

If every major mobile port achieves similar compression—and that’s a big “if” given the Sora project’s ideal conditions—companies need fewer mobile teams. If every codebase migration runs 50% faster with half the staff, infrastructure teams shrink. If every documentation project, every refactoring sprint, every test suite generation requires fewer bodies—the numbers compound.

The conditional matters. These gains aren’t guaranteed. But they’re what investors are pricing in.

The Global Developer Population Sets the Ceiling

SlashData’s 2025 analysis counts 47.2 million developers worldwide. Of those, 36.5 million are professional (employed full-time in development roles). The remaining 10.7 million are amateur or part-time.

Here’s an unsettling data point: amateur developer population is shrinking. It dropped by 1 million in 2024. The traditional pipeline—hobbyists becoming juniors becoming seniors—appears to be contracting, though the causes remain unclear.

The demographic profile is aging. Developers aged 18-24 dropped from 33% to 23% between 2022 and 2025. The 35-44 cohort grew from 22% to 26%.

Several explanations fit this data: fewer people entering the field, existing developers staying longer, reduced hiring at entry level, or AI tools reducing the need for junior positions. Correlation shows up in the numbers. Causation doesn’t—yet. But the trend line doesn’t favor junior developers regardless of the underlying driver.

The Investor Logic—Follow the Money

SoftBank’s Masayoshi Son stated explicitly: they’re pursuing “artificial superintelligence.” OpenAI is their bet on that future.

At $500 billion, investors aren’t pricing ChatGPT subscriptions. They’re pricing a future where software development itself transforms. Where the estimated $3.5 trillion global software industry—running on perhaps $1.5-2 trillion in labor costs, by some analyst estimates—becomes partially automated.

Capture 10% of that labor spend? $150-200 billion addressable market. At 20% capture, you’re looking at $30-40 billion in revenue—not far from what OpenAI needs.

The math works on paper. The human cost is what nobody wants to quantify.

But the directional signal points one way: AI tokens are becoming substitute goods for certain types of engineering labor. And token prices have been falling 10-15% quarterly while US labor costs continue climbing 3-4% annually.

The Timeline Question

OpenAI projects profitability by 2030. They need to raise $50-80 billion more to get there. The cash burn rate hit $8.67 billion in just the first nine months of 2025.

That runway depends on continued faith from investors who are pricing in workforce transformation. If that transformation doesn’t materialize—if junior engineers remain essential, if AI tools plateau in capability, if companies keep hiring at current rates—the $500 billion valuation faces serious pressure.

The uncomfortable implication: OpenAI’s financial viability likely requires AI to displace meaningful engineering capacity. Not necessarily as explicit strategy, but as the economic outcome that justifies current investment levels.

What Does This Mean for Developers?

The productivity story isn’t clean. The METR randomized controlled trial—studying 16 experienced developers across 246 real tasks—found developers were actually 19% slower with AI tools, while believing they were 20% faster. The researchers measured actual task completion time in controlled conditions. Real clock measurements, real tasks. But I’d be willing to be that these numbers more reflect a transient state of evolving tools and the understanding of how to use them. This was back in July — a lifetime ago.

The DORA report shows AI adoption correlates with decreased delivery stability. Only 24% of developers fully trust AI outputs.

These contradictions matter. The tools create value in specific contexts (code translation, boilerplate generation, documentation) while struggling in others (novel architecture, complex debugging, system integration). The Sora project hit the sweet spot. Most projects won’t.

But investment doesn’t require universal perfection. It requires enough displacement across enough use cases to justify the numbers.

If AI tools replace 20% of junior engineer output across the industry, companies will hire 20% fewer juniors. Not immediately. Not dramatically. Just... gradually. Fewer entry-level positions. Longer ramp times for those hired. More responsibility pushed to AI systems.

The $500 billion bet is that this happens faster than most people expect.

The Quiet Part

Nobody at OpenAI will say “we’re in the business of replacing engineers.” The messaging centers on augmentation, productivity, developer experience.

But the valuation math implies displacement. The token economics assume AI output substitutes for human output at scale. The financial projections depend on companies spending less on engineering labor and more on AI infrastructure.

When you hear “$500 billion valuation,” one way to interpret it: investors are betting AI will eliminate or substantially reduce millions of engineering positions within the decade. OpenAI won’t put that in a press release. The investment thesis requires it anyway.

The Sora project showed it’s possible in ideal conditions. The question is whether those conditions generalize—and whether the productivity gains survive contact with messy, real-world development.

For technical analysis of AI coding tools and their real-world performance, follow HyperDev. My previous coverage of token economics and AI development costs provides additional context on these trends.