The real work was never about writing code.

That statement would have been controversial three years ago. Today, with the Stack Overflow 2025 Developer Survey showing 65% of developers using AI tools weekly and my own projects showing 6-10x productivity gains on greenfield implementation tasks, it’s becoming harder to argue. The interesting question isn’t whether AI changes software engineering—it’s what remains when implementation gets automated.

Here’s my new working theory, built from recent research and hands-on experience orchestrating AI agents across complex projects: senior engineering is converging toward a role that looks more like subject matter expert plus systems architect than traditional developer. The code-writing layer is becoming infrastructure—important, but increasingly invisible. What emerges is something both familiar and radically different.

I wrote recently about the Jacquard loom lesson—how the Canuts who fought automation lost, while pattern masters who designed the punch cards thrived. The same dynamic is playing out now. The question isn’t whether to use AI tools. It’s whether you become the pattern master who designs what they execute.

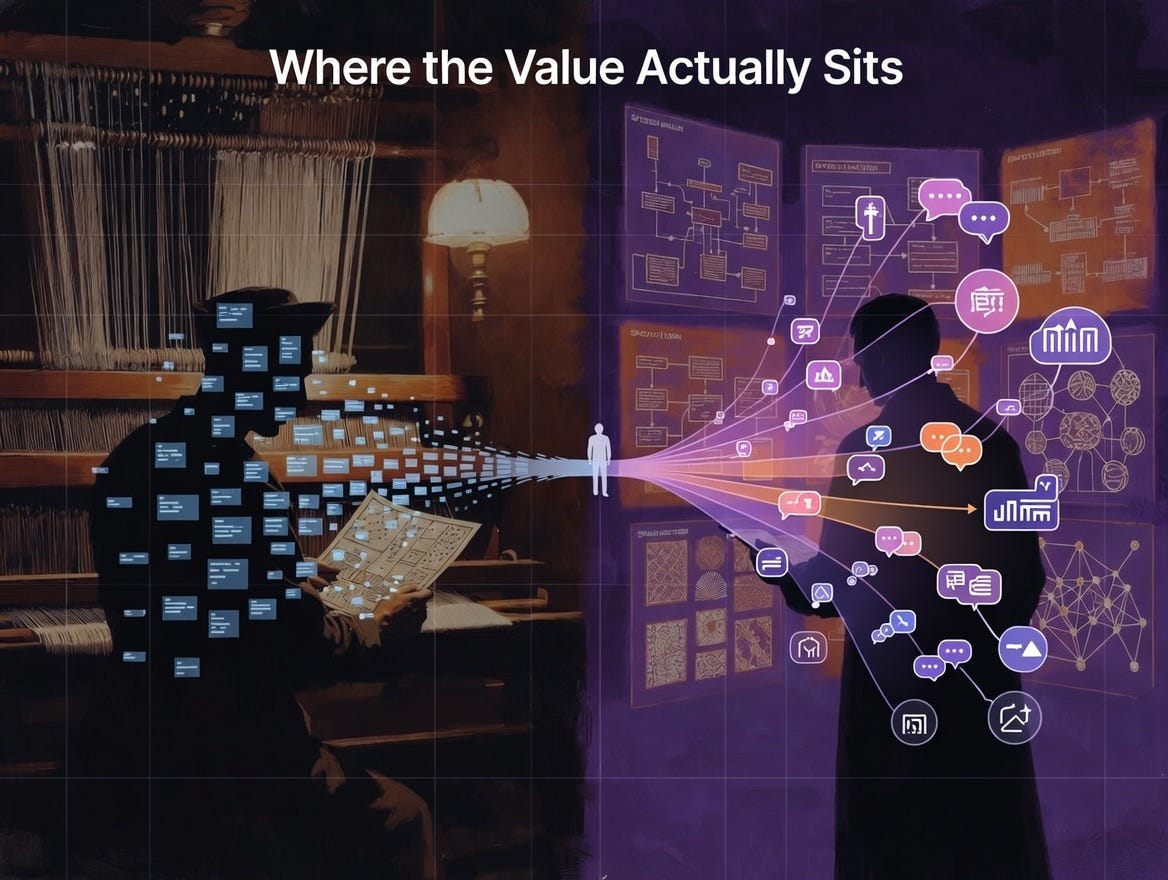

Where the Value Actually Sits

The most revealing data point isn’t about whether AI tools work—it’s about who they work for.

The Faros AI Productivity Paradox Report (July 2025) analyzed data across thousands of developers and found something telling: “Adoption skews toward less tenured engineers. Usage is highest among engineers who are newer to the company... lower adoption among senior engineers may signal skepticism about AI’s ability to support more complex tasks that depend on deep system knowledge and organizational context.”

That’s not a failure of AI tools—it’s a signal about where constraints actually exist. If your bottleneck is navigating unfamiliar code and accelerating early contributions, AI helps enormously. If your bottleneck is the “deep system knowledge and organizational context” that seniors carry—code generation speed is irrelevant.

A University of Chicago working paper (November 2025) found something even more interesting: experienced developers were 5-6% more likely to successfully use AI agents for every standard deviation of work experience. Why? They used “plan-first” approaches—”laying out objectives, alternatives, and steps” before invoking AI. Juniors did this far less frequently. The paper concludes: “expertise improves the ability to delegate to AI.”

Here’s the thing: senior engineers already spend most of their time on non-coding work. Jue Wang, a partner at Bain, told MIT Technology Review last week that “developers spend only 20% to 40% of their time coding.” The rest goes to analyzing problems, customer feedback, product strategy, and administrative tasks.

AI doesn’t change what senior engineering is. It reveals what it always was.

A Case Study in What Actually Happened

I recently completed a project that illustrates where the human work actually sits. Building a semantic search knowledge base for a travel agency client, I tracked every commit across 9 calendar days: 120 total commits, roughly 90% Claude-assisted.

The productivity numbers look impressive: 6-10x multiplier compared to my baseline velocity on similar projects. At my consulting rate, what I estimate would have taken 150-200 billable hours compressed to about $100-200 in API tokens plus 50-70 hours of wall-clock time—most of which wasn’t coding.

But here’s what’s interesting about the 12 human-only commits (10% of total):

Configuration tweaks requiring domain knowledge (model selection for specific use cases)

Debug logging (quick diagnostics when something felt wrong)

Release management

One research document on Slack architecture options

The human contributions weren’t about implementation—they were about judgment. Choosing the right model for email writing versus general queries. Knowing when the AI’s suggestion would create problems downstream. Understanding the client’s actual workflows well enough to structure the system appropriately.

What surprised me: the time savings didn’t come from faster typing. They came from eliminating the iteration cycles between “write code” and “realize it doesn’t fit the requirements.” Specifying clearly upfront meant fewer rewrites—but that specification work was irreducibly human.

The Specification-Driven Development Thesis

The pattern I’m seeing aligns with what several industry voices are now articulating.

Addy Osmani at Google argues developers are evolving from “coders” to “conductors” orchestrating AI agents. Kent Beck—one of the Agile Manifesto authors—suggests “augmented coding” deprecates language expertise while amplifying vision, strategy, and task breakdown. Sean Grove from OpenAI put it directly: “The person who communicates the best will be the most valuable programmer.”

Specification-Driven Development is now on the ThoughtWorks Technology Radar. Tools like AWS Kiro, GitHub Spec-Kit, and Tessl are building products around this premise. Andreessen Horowitz frames this as “the largest revolution in software development since its inception”—venture rhetoric, obviously, but the underlying bet (prompts as source code, specifications as maintained artifacts) is getting serious investment.

Worth noting what doesn’t work as smoothly: legacy codebases with decades of undocumented business logic, highly regulated environments where audit trails matter, and anything requiring coordination across organizational boundaries. The pattern I’m describing fits greenfield projects and well-documented systems better than the brownfield reality most enterprises face.

This isn’t abstract. Builder.io has defined an “Orchestrator” workflow: spec → onboard → direct → verify → integrate. That sequence describes what I actually did on the knowledge base project. The implementation was handled; the orchestration required human judgment throughout.

What AI Actually Can’t Do (Yet)

The Qodo 2025 State of AI Coding survey found only 3.8% of developers report both low hallucination rates and high confidence shipping AI code without review. 65% cite missing context as the primary barrier.

That “missing context” is the key. Consider what the AI couldn’t know during my knowledge base project:

Business model specifics: How the travel agency’s supplier relationships actually work. Which data matters for their specific service model. Why certain integrations were higher priority than others.

Organizational constraints: Budget limitations. Timeline pressures from a specific upcoming sales season. The technical capabilities of the staff who would maintain the system.

Historical context: Why previous approaches to similar problems hadn’t worked. What the client had tried before and rejected. Political dynamics around system adoption.

None of this lives on the public web. It exists in Jira tickets, PowerPoint decks, Slack conversations, and institutional memory. The METR study (July 2025) specifically identified “tools’ lack of vital tacit context or knowledge” as a key factor in why experienced developers were slower with AI assistance. Ryan Salva, senior director of product management at Google, told MIT Technology Review: “A lot of work needs to be done to help build up context and get the tribal knowledge out of our heads.”

The Spider 2.0 benchmarks confirm this: AI scores drop significantly on actual enterprise workflows compared to clean academic datasets. Real systems have messy schemas, undocumented business rules, and constraints that only make sense if you understand why they exist.

The Security and Quality Problem Compounds This

Here’s a less-discussed limitation: Veracode’s 2025 GenAI Code Security Report, which tested over 100 LLMs across 80 controlled coding tasks, found that 45% of AI-generated code introduced security vulnerabilities in their experimental setup. Java was worst at 72% failure rate. The controlled environment matters—real-world results vary with prompting quality and review practices—but the underlying issue is real: security requires understanding threat models, compliance requirements, and risk tolerances that vary by organization.

Miguel Grinberg, a 30-year development veteran, observed that code review takes as long as writing code when AI is doing the implementation. More importantly, there’s an accountability dimension: “AI won’t assume liability if code malfunctions.” Someone has to own the outcome, and that ownership requires understanding what the system is supposed to do.

The Multi-Agent Future Amplifies This Pattern

The trajectory I’m betting on: moving from single-agent assistance toward multi-agent orchestration. That shift would concentrate human work even further up the stack—if the infrastructure materializes.

IBM’s research on AI orchestration describes the emerging pattern: multiple agents with specific expertise working in tandem under orchestrator uber-models. Google’s Agent Development Kit (ADK) is building infrastructure for “multi-agent by design” systems—modular, scalable applications composed of specialized agents in hierarchy.

The A2A Protocol (donated to the Linux Foundation by Google, with over 50 launch partners including Atlassian, Salesforce, and SAP) enables agent-to-agent communication. Combined with Anthropic’s MCP for agent-to-tool connections, we’re building infrastructure for systems talking to systems at scale.

Early pilot results are dramatic but need context. Research on enterprise AI agents shows Generative Business Process AI Agents (GBPAs) achieving 40% reduction in processing time and 94% drop in error rate on financial workflows in controlled environments. Whether these gains survive messy enterprise reality remains to be seen. But the implication is clear: when agents can autonomously analyze supplier performance, renegotiate terms, and execute approvals, what’s left for humans?

Domain expertise and strategic oversight. Multi-agent systems handle coordination; humans provide the context those systems can’t access and the judgment calls that require understanding organizational stakes.

The Role Transformation Is Already Happening

New job titles are emerging. McKinsey’s research predicts the labor pyramid shifting toward senior engineers for complex architecture and code review. Organizations are defining roles like:

AI Software Architect: Requires context engineering, specification-driven development

Agent Review Engineer: Specification ownership, hallucination checking, ensuring agent outputs align with business requirements

Coinbase’s Head of Platform, Rob Witoff, told MIT Technology Review last week that while they’ve seen massive productivity gains in some areas, “the sheer volume of code now being churned out is quickly saturating the ability of midlevel staff to review changes”—pressure moving upward, not distributing evenly.

Gergely Orosz’s analysis identifies what’s becoming more valuable: tech lead traits, product-mindedness, solid engineering judgment (not just coding). What’s declining: pure prototyping skills, language polyglot expertise. The differentiator isn’t knowing syntax—it’s knowing why.

Educational Institutions Are Responding

The signals from education are telling:

Harvard launched COMPSCI 1060: “Software Engineering with Generative AI” (Spring 2025)

Stanford introduced “Vibe Coding: Building Software in Conversation with AI”

UC San Diego consortium (Google.org funded) created six turnkey courses integrating AI, with Leo Porter identifying problem decomposition as the new priority for introductory classes

Hack Reactor now teaches Copilot after proficiency without it—recognizing that understanding fundamentals matters more when AI handles syntax. The Raspberry Pi Foundation argues learning to code provides “computational literacy” and agency regardless of AI capabilities.

There’s genuine tension here. Studies show students perform better with Copilot immediately, but concerns about “cognitive laziness” and long-term skill development are mounting. The question isn’t whether to use AI tools—it’s how to develop judgment that makes AI tools useful.

What the Pattern Master of 2028 Looks Like

What surprised me after running the knowledge base project wasn’t the productivity gain—it was how different the work felt. I wasn’t engineering in the traditional sense. I was doing something more like:

Subject matter expert for technical domains who can translate ambiguous business requirements into precise specifications AI can execute.

Orchestrator of agent teams who understands which specialized capabilities to deploy against which problems, and how to coordinate multi-agent workflows.

Context bridge who identifies when agents miss critical organizational knowledge—the meeting that changed priorities, the constraint that exists for regulatory reasons, the technical debt that can’t be addressed yet.

Accountability owner who takes responsibility for outcomes in ways that AI cannot, making judgment calls that require understanding stakes and tradeoffs.

Systems coherence maintainer who ensures that agent-driven development produces architectures that remain understandable, maintainable, and aligned with long-term organizational needs.

None of this is entirely new. Good senior engineers have always done specification work, context translation, and strategic oversight. What changes is the ratio—these become the primary activities rather than overhead between coding sessions.

The Pragmatic Implications

If this analysis is directionally correct, several implications follow:

For individual practitioners: Invest in domain expertise alongside technical skills. Understanding your industry, your organization’s constraints, and your stakeholders’ real needs becomes the differentiator. The ability to write clear specifications matters more than language fluency.

For engineering managers: Rethink how you evaluate senior contributions. Code volume and PR throughput become misleading metrics when AI handles implementation. Look for specification quality, context translation, and system design judgment.

For organizations: The constraint isn’t AI capability—it’s organizational readiness to provide the context AI needs. Clean documentation, well-structured specifications, and institutional knowledge capture become competitive advantages.

For education and training: Problem decomposition, requirements analysis, and domain modeling deserve more emphasis. Syntax and language features deserve less. Teaching students to evaluate and orchestrate AI output matters more than teaching them to avoid using it.

The Bottom Line

AI automates the implementation layer. Multi-agent systems are beginning to automate the coordination layer. What remains is the judgment layer—the work that requires understanding business context, organizational constraints, and strategic tradeoffs that exist outside any training dataset.

That work was always the actual job. We just called it “senior engineering” and measured it poorly because code output was easier to count.

The pattern master of 2028 won’t write 10x more code. They’ll translate ambiguous requirements into specifications that agent teams can execute reliably. They’ll identify when AI outputs miss critical context. They’ll maintain system coherence across increasingly automated development workflows.

The code-writing skill doesn’t become worthless—it becomes infrastructure, like understanding TCP/IP or knowing how compilers work. Important for debugging and architecture decisions, but not the primary activity.

This pattern may be emerging fastest in startups and well-resourced enterprise teams with clean codebases and modern tooling. Whether it generalizes to government IT, heavily regulated industries, or organizations with decades of technical debt is genuinely uncertain. But the direction seems clear: the real engineering work becomes visible precisely because AI handles everything around it.

Research sources include the Faros AI Productivity Paradox Report (July 2025), University of Chicago Booth working paper on AI agent productivity (November 2025), METR’s randomized controlled trial on experienced developer productivity (July 2025), Veracode’s GenAI Code Security Report (July 2025), MIT Technology Review’s developer survey (December 2025), and industry analysis from ThoughtWorks, Qodo, and Builder.io. Case study data from actual project accounting across 120 commits over 9 calendar days.