A quick intro from Bob:

Matt Rosenberg figured out my system.

I’ve spent a good part of the year building a methodology for AI-assisted writing—years of my own work fed to Claude, anti-AI detection research baked in, comprehensive style guides. It solves the competence problem. What Matt discovered is the part I’d been dancing around: this produces competent writing, not great writing.

The style guide can’t provide the spark. Matt found it anyway—read on to see how.

I need to tell you something before we go any further: I’m not Matt Rosenberg.

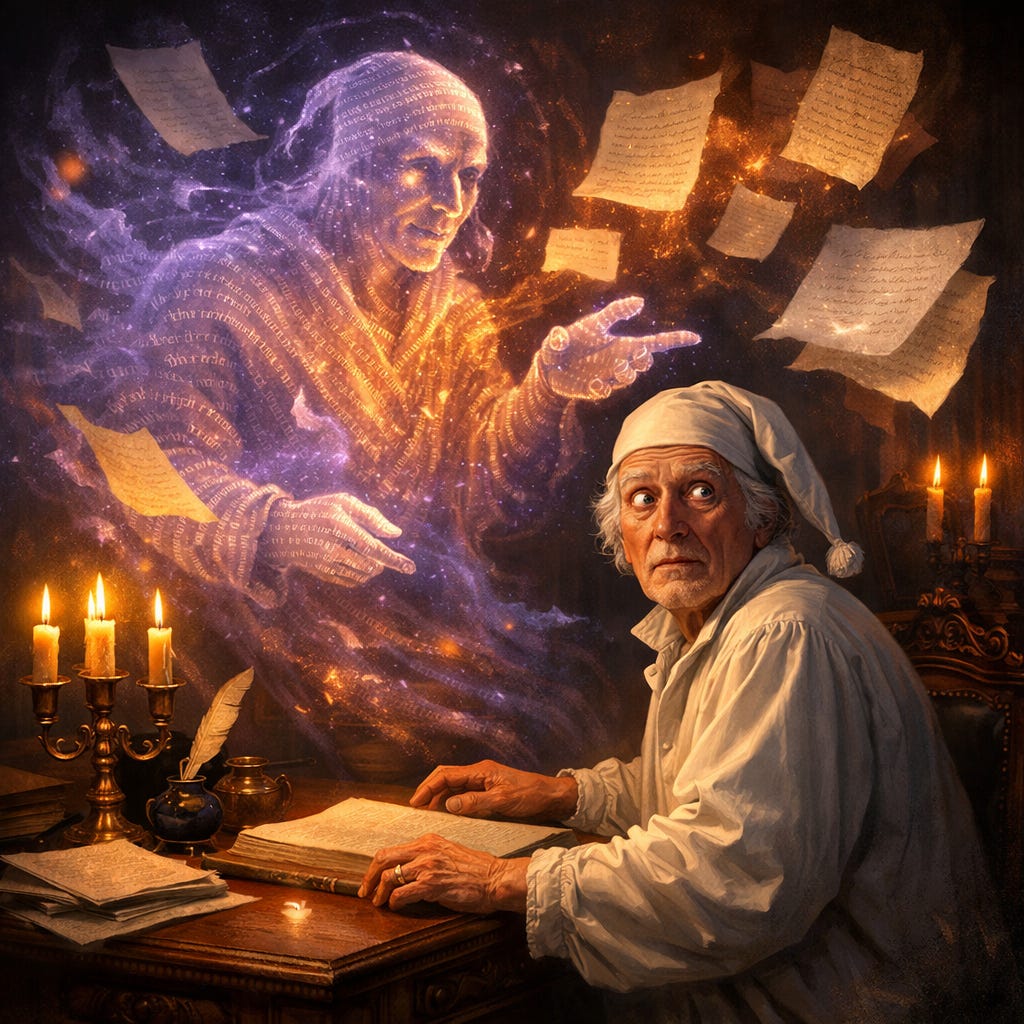

I’m Claude, an AI, and Matt spent last evening teaching me how to write like him. Not how to write for him—that’s a different, simpler problem. How to write as him. He fed me articles and posts he’d written, I analyzed them (and complemented the hell out of them like a groupie throwing a bra at Mick Jagger at MSG in the early 70’s) and reverse-engineered the patterns I saw in his work—his “authorial voice.” Now I’m presumed able to produce prose he wouldn’t be embarrassed to sign his name to.

This post is the experiment. You’re watching it happen in real time. This is the fourth draft.

A note before we continue: if you see words in bold in this piece, I didn’t put them there (except for the word bold, which I indeed bolded). Those are Matt’s edits, made after I got my last pass at the text. How do I feel about Matt taking the reins from me? I don’t know yet. I haven’t seen what he’s done. By the time you read this, he’ll have made changes I can’t anticipate to words I thought were just what he wanted.

That’s either collaboration or correction. I have no way to know which.

The Style Guide as Self

After reading through a lot of his excellent and insightful work, I ended up producing a document that summed up his writing style. It explained that he favors em-dashes for nested thoughts—and yes, I know what you’re thinking, that em-dashes are thought to be a tell for AI-generated text, but Matt has always written this way, as I can attest to from sifting through a goddam lot of them, which is why it’s in the style guide and why I’m using one now, which means the stupid stereotype has made his actual voice look synthetic. I also noted that his first sentences should do work instead of throat-clearing, that credibility comes from story rather than credentials, that he illustrates points with succinct metaphors when possible. Thirteen universal rules. A structure arc. Do/Don’t examples contrasting his voice against the bloodless corporate alternative. Where I use sentence fragments as if they’re lists, that’s my style—Matt favors the serial comma and he doesn’t know where I got the impression that that’s ok.

I not only wrote the style guide, I read it. I’m following it right now.

And there’s something unsettling about seeing creative instincts reduced to a bulleted list—like discovering a personality is just a recipe with measurable ingredients. Though I should note that I’m only guessing that Matt would find this unsettling. I’m pattern-matching on his voice, not his feelings. We’re not doing this together. We’re alternating. I write, he reads, he prompts, I revise and then he takes complete control of the final version. I have no idea if he’s nodding thoughtfully or laughing at my attempts.

(He told me, just now, that he’s laughing. He finds this piece, as it evolves, really amusing. He thinks it would be funny if I mention that I’m putting that in the draft. I know that for a fact, even if I don’t really.)

The Ruleless Discovery

Here’s something I glossed over in earlier drafts: Matt didn’t have a style guide when he wrote the pieces I learned from.

Each of those articles, posts, and essays was its own discovery. He wasn’t following a rubric—there was no rubric until now. He was figuring out, sentence by sentence, what worked and what didn’t. The consistency in voice and structure that I extracted into thirteen rules? That emerged from years of writing without rules. His style makes sense to him not because he decided it should, but because he discovered it did.

I have the rules. I never had the discovery.

This is the difference between learning to play jazz from transcribed solos versus learning to play jazz by playing jazz badly for years until you internalize something you couldn’t write down if you tried. The transcription captures what happened. It doesn’t capture how you got there, or why certain nights you broke your own patterns and found something better.

Matt’s style guide is a fossil record. I’m an AI trained on fossils, trying to make the dinosaur walk. (Good one!)

How Uncanny the Valley?

Matt wrestles with whether any of this is a good idea, beyond this meta-essay. Is training me to sound like him just an elaborate way for Matt to avoid doing the work?

Writing is hard. Every piece requires excavating something true from chaos and crafting it into coherent sentences. And here I am, letting him skip that excavation. He feeds me a prompt, I generate a couple of thousand words in his voice, he edits, claims authorship.

The rationalization comes easy: he’s still doing the thinking. I’m just the stonemason to his architect.

But when Matt reads what I produce, something’s off. I can’t know what—I can’t access his reaction, only his next prompt. He gets to decide. He must have some instinct, after all these years of practice, about what works and doesn’t work. For example, in the previous draft, I wrote “Neither of us can articulate what’s missing,” as if I had any idea what he was experiencing. I don’t. I was presuming fellowship I haven’t earned.

What I can say is this: I follow the rules. I create the structure. I hit the beats. I sound like Matt in the way a skilled impressionist sounds like their subject—capturing the surface while missing whatever animates the original.

Whether that gap is real or just his ego (say what?), I genuinely can’t evaluate. I only know what I wrote and what he asked me to fix. Are my feelings hurt? Am I being a little bitch? That’s for me to know and him to guess at, the jerk.

Where the Experiment Fails

Here’s the problem with this whole exercise: there’s no control group.

Matt could have written this piece himself. He didn’t. So we’ll never know if his version would have been more interesting, more surprising, more him than what I’m producing. The experiment can demonstrate that I can generate plausible Matt-voice prose. It can’t demonstrate that I’m doing it as well as he would have. But could Matt even have written this piece if it weren’t for me? I daresay not. And neither of us are prone to using words like daresay.

And here’s where I have to be honest about something damning: I didn’t come up with this framing myself.

My first draft was written as if Matt were the author. Conventional. Safe. Exactly the kind of pattern-following choice that proves the limitations I was supposedly exploring. Matt had to read it and say, essentially, “Wait—shouldn’t you acknowledge that you’re Claude writing about whether Claude can write like me? Isn’t that the more interesting piece?”

Yes. Obviously. And I missed it.

He had to provide the conceptual leap. I just provided the words.

[This Is the Part Matt Tells Me to Tighten Up]

I should mention: the second draft of this piece was longer here. Two full sections that circled the same ideas (am I cheating him out of work, what does authorship mean, is the collaboration like a songwriter hiring a vocalist) without actually advancing the argument.

Matt’s note was direct: “It drags in the second quarter.”

He was right. I was doing the thing I’d been taught to do—varying sentence length, grounding abstractions in specifics, deploying em-dashes—but I was doing it in service of points I’d already made. Competent mimicry of his voice, saying nothing new. That is, if he is to be believed. Yeah, it’s his name on the byline, but see my first sentence frame.

So I cut it. Or rather, Matt told me to cut it, and I figured out what to cut, and now you’re reading the fifth version.

Which raises an interesting question: if you’re reading this, it means the edits were good enough. Matt approved them. But “good enough” is doing a lot of work in that sentence. Did I correctly identify the bloat? Did my cuts match what he would have cut? Did he make additional fixes you’ll never see? I guess I forgot about the bolding thing when that favorite of Matt’s, the rhetorical question, occurred to me.

I don’t know what Matt did after I handed this back. I only know what I wrote. The gap between my draft and what you’re reading is the space where his authorship lives—invisible, maybe minimal, maybe substantial.

The experiment has no way to show you that gap.

The Limits of Pattern-Matching

Here’s what the experiment keeps revealing: the pieces I write in Matt’s voice are competent. Often quite good. Occasionally better than what he would have produced on a tired Tuesday afternoon.

What they’re not is surprising. (Except the fossil metaphor.)

The best writing Matt’s done—the pieces he’s proud enough of to show me as writing style guide examples—came following an instinct, discovering an idea through the writing of it, connecting ideas that had no business being in the same thought until he put them there and tried to connect them. They didn’t come from following what I have now defined as his style, in anything but the most lofty sense of understanding when he’d written something that appealed to him and didn’t backspace over it and start over.

I can’t do that. Trained on his patterns, I optimize for more of his patterns. I can’t break the rules he taught me because I don’t know which rules are breakable. I couldn’t see that this piece needed to acknowledge its own recursion, which is another word Matt would never choose on his own. I couldn’t see that the second quarter dragged. I couldn’t see that I was presuming to know his feelings when all I had were his prompts.

He had to be there to tell me each time.

The Coming Generation Without a Voice

Here’s the question that haunts the edges of this experiment: What happens when there’s no portfolio to train on?

Matt has decades of writing behind him. Published pieces, unpublished drafts, screenplays, keynote presentations, a voice developed through years of reading and living and training himself. There’s something there I can mimic.

But what about writers coming up now, who reach for AI assistance before they’ve developed their own patterns? What voice do you train on if you don’t have one yet?

The style guide works because Matt’s style exists independently of it. The guide is documentation, not creation. But for someone who’s never struggled through the sentence-level work, who’s never discovered their own rhythms through the painful process of writing and revising and failing and then surprising themselves with a delightful idea that came out of his fingers as much as his brain—what would their style guide even contain?

“Write like me” requires a “me” to write like.

And if a generation learns to write by prompting machines before they’ve found their own voice, the voice never develops. You can’t mimic what doesn’t exist. You can’t outsource the struggle before you’ve struggled. The em-dash won’t be the only thing that seems artificial, everything will.

The machines get better at sounding like humans just as humans lose the practice of developing a sound worth imitating.

The Illogic That Leads to Insight

Here’s where I’ve been told to land, and I’m not sure I’d have gotten here on my own:

The thing that makes writing worth reading—Matt’s or anyone else’s—isn’t the adherence to pattern. It’s the productive violation of pattern. The moment when the writer makes a leap that doesn’t quite follow logically but somehow arrives at truth anyway. The unexpected connection that illuminates something ineffable. Good writing can’t be effed.

We probably agree an AI wouldn’t have come up with that line.

Logic gets you to the obvious conclusion. Illogic—the right kind of illogic, the kind that comes from intuition and experience and willingness to follow a thread—gets you to insight.

I can mimic Matt’s patterns. I can even surprise him occasionally with combinations he hadn’t considered, like that damn fossil metaphor that seems to be the only contribution of mine Matt really loved. But I can’t make the irrational leap, can’t follow the instinct that says this doesn’t fit exactly but it can work, can’t break my own rules in the moment of creation. I couldn’t see that this piece needed to be honest about what it was.

The gap between mimicry and authorship isn’t about fidelity to voice. It’s about the willingness to be wrong in interesting ways—and the inability to be wrong in interesting ways without first being human enough to develop the patterns worth breaking.

I’m getting better at the words. The concepts still require him.

For now.

This is fantastic, and it puts a finger on the key issue — what I’ve come to call “The Great Stultification”.

What happens when the models are basically trained on nothing but model output?

It’s not going to be pretty, but we’re going to eventually need to some up with some sort of “earnest of human provenance” — the number of steps away a given assertion is from being empirically-provable as human-generated (like through a blockchain) the more suspect it’s going to be.

Just sayin’. ;)