I spent last week at a Google event that was supposed to demonstrate their AI leadership. Instead, it showed me why they might actually be in trouble—and it’s not the obvious reason.

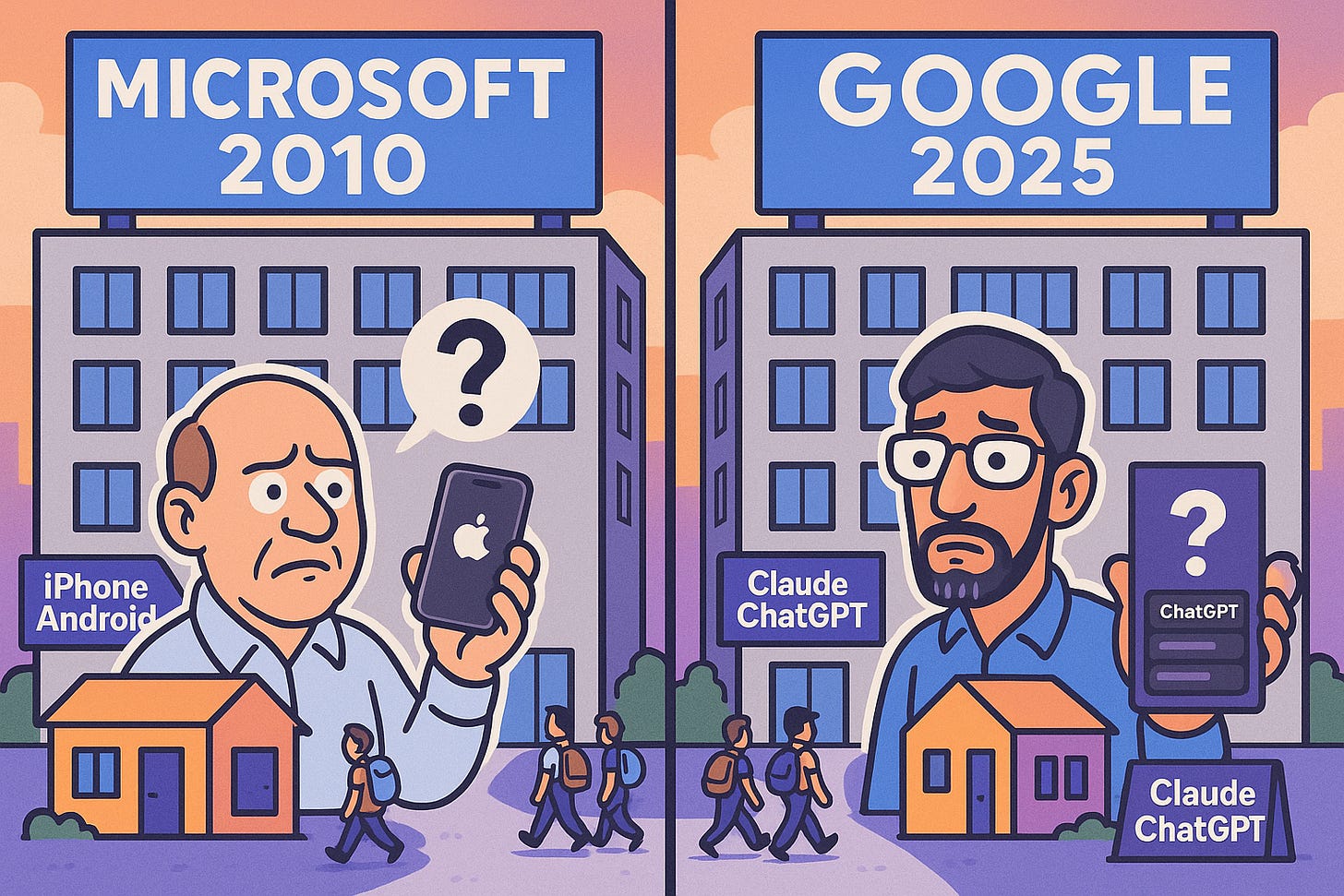

The comparison everyone’s making right now is Sundar Pichai as the new Steve Ballmer. 76% of tech workers agree with that, and the parallels are striking. Both business-focused CEOs following visionary founders. Both caught flat-footed by major technology shifts. Both protecting massive revenue streams—Microsoft’s 90%+ Windows share then, Google’s 89-90% search dominance now.

But here’s what that comparison misses.

Google Still Has Cards Microsoft Never Did

The structural differences are huge. Microsoft in 2010 faced existential threat—mobile was literally replacing desktop computing, and they had zero presence. Android was rapidly gaining ground in 2011. Windows Phone launched years late and never gained traction.

Google’s situation looks different. In 2024, Google handled 14B+ searches daily—roughly 300× ChatGPT’s search-like query volume, even with Altman’s stated 1B+ prompts daily. Their search market share remains stable around 90%, and advertising revenue keeps growing at 10-12% annually. The stock hit all-time highs on October 30, 2025.

More importantly, Pichai isn’t Ballmer. When Ballmer dismissed the iPhone in 2007 saying “There’s no chance that the iPhone is going to get any significant market share,” he revealed a fundamental blindness to platform shifts. Pichai saw the threat immediately—Google declared “code red” on December 21, 2022, within weeks of ChatGPT’s launch, and shipped Bard in months.

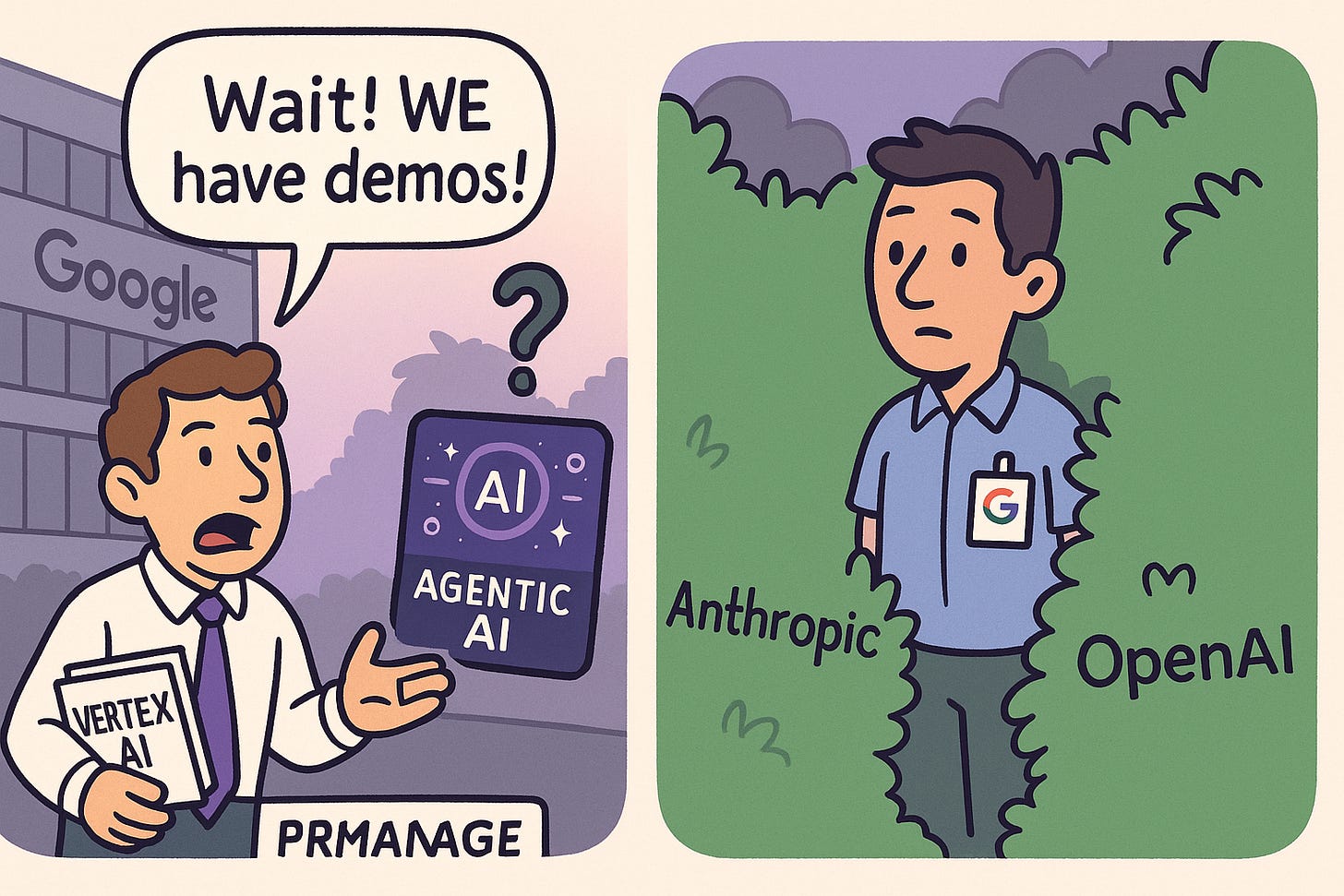

And they hedged their bets in ways Microsoft never could. As of mid-2025, Google owns approximately 14% of Anthropic after investing $3B+, alongside fresh multibillion-dollar TPU capacity deals. That’s not something Ballmer would have done. Microsoft in 2010 was trying to fight Apple and Google head-on with Windows Phone and Bing. Google has ownership stakes in their supposed competitors.

But Then I Went to That Event

Last week I attended what was billed as a leadership showcase featuring Google’s internal go-to-market lead and representatives from two vendors using Google’s AI tools—Vertex and the rest of their stack. This was supposed to demonstrate how agentic technologies could transform businesses.

The presentations were polished. Smooth. Professional. The presenters sounded like they knew what they were talking about.

Two things stood out immediately.

First, they used “agentic” as a synonym for “AI applications.” Which it’s not. Agentic systems plan, decide, and act across multi-step tasks with tools and limited supervision—autonomous decision-making, iterative problem-solving, tool orchestration. What they were showing was just... AI features. Search with a chatbot wrapper. Document analysis with some automation. Not agentic.

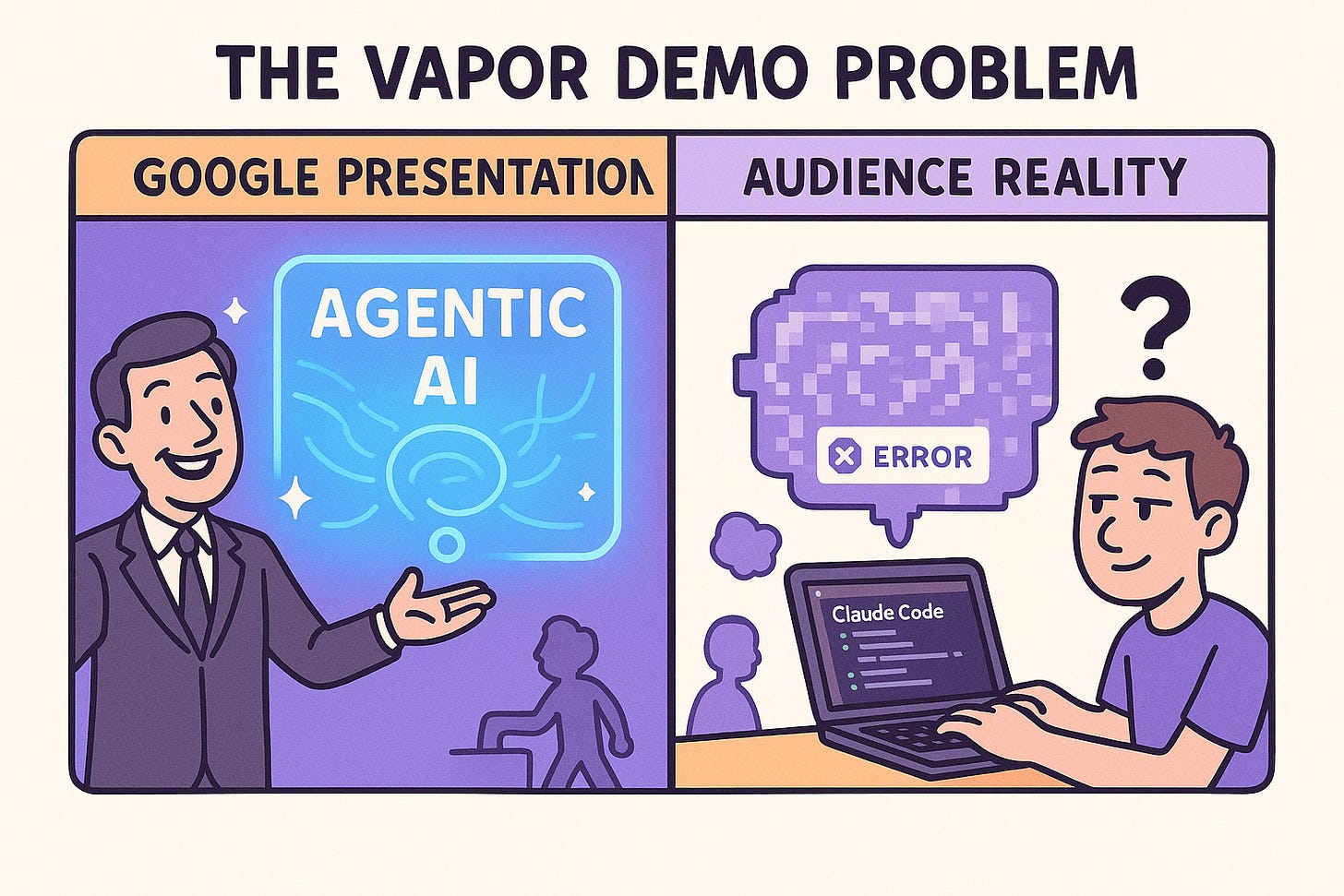

Second, most of it was conceptual. Highly polished mockups. Beautiful slides showing what could theoretically happen.

The one “functioning” demo was a proof-of-concept search interface that basically did what a fancy search engine does. And it didn’t work properly during the presentation.

What I Was Building While They Were Presenting

Here’s the thing that kept bothering me. While they were on stage showing broken concept demos, I was sitting in the audience using Claude MPM—running Claude Code under the hood—doing actual agentic development work for clients.

Not concepts. Working code. Real implementations.

Specifically: a multi-agent system where one agent analyzed requirements and generated a project plan, another agent implemented code modules in parallel isolated contexts, and a coordinator agent managed dependencies and integrated results. Autonomous task decomposition. Tool selection and execution. Error recovery and iteration. The actual characteristics that define agentic systems.

And what I was building? More advanced than what they were showing.

That shouldn’t be possible. Google commands massive technological advantages. They invented the transformer architecture that powers all modern LLMs. They have DeepMind. Alphabet guided approximately $75B in 2025 capex largely for AI infrastructure—very different from Microsoft’s 2010 mobile disruption dynamic. They maintain R&D spending of $49.3B in 2024, roughly the same 14% of revenue ratio Microsoft had in 2010.

If you have those resources and you’re trying to convince people to use your tech, the examples you show should be not just functional but genuinely impressive. They should demonstrate capabilities others can’t match.

Instead, they’re showing mostly conceptual demos while we’re building real things with their competitors’ tools.

The Marketing Company Problem

The event felt more like a marketing pitch than a technology showcase. And that’s the tell.

Microsoft in 2010 had a similar problem—Gartner analyst Roberta Cozza identified “brand perception” as their “main barrier” rather than technical capability. When Google’s Eric Schmidt listed the “Big Four” tech companies in 2011, he explicitly excluded Microsoft, explaining they weren’t “driving the consumer revolution in the minds of consumers.”

The comparison everyone’s worried about—Google as the stuffy mega-corporation while Microsoft delivers exciting new products—that role reversal has already happened at the product level. ChatGPT commands roughly 80% of AI search and chatbot traffic share versus Gemini’s significantly smaller portion, according to Similarweb data from 2025. Menlo Ventures’ mid-2025 enterprise survey shows Anthropic at 32% usage share, OpenAI at 25%, and Google at 20% among roughly 150 enterprise decision-makers.

But here’s the deeper issue. When you’re leading with marketing instead of technology, it suggests something worse than strategic paralysis. It suggests your internal team isn’t capable of building the examples.

The Developer Exodus Nobody’s Measuring

Forbes called Ballmer “the worst CEO of a large publicly traded American company” in 2012, arguing he “steered Microsoft out of some of the fastest growing and most lucrative tech markets.” The stock price reflected that reality—essentially flat from 2000-2013 while Apple’s valuation soared 6,000%.

But the stock price was a lagging indicator. The leading indicator was where developers were going. Stack Overflow’s 2011 survey showed 34.3% using iPhones and 30.4% Android—the platforms where innovation was happening. Windows Phone was barely mentioned.

Today, developer experiments comparing AI platforms consistently rank Anthropic’s Claude highest for complete projects, with Google’s Gemini described as “ideal for MVPs” but something to “avoid for projects with many iterations because it introduces bugs.”

When Staying Becomes the Problem

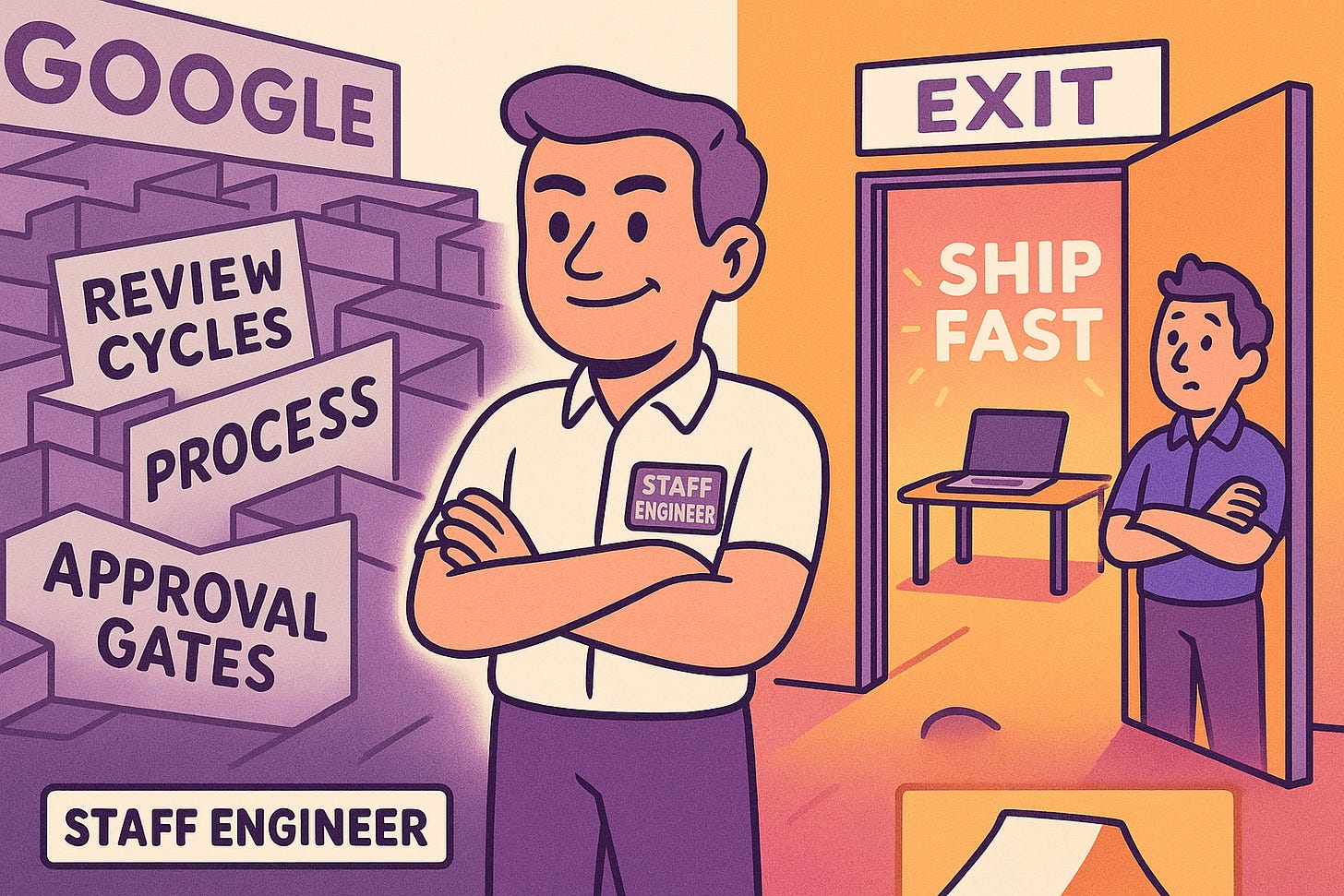

My own journey into agentic development started with a connection that crystallized this issue. I met a Google staff engineer who’d recently left the company. Not for more money. Not for a better title.

He left because working at Google was actively slowing him down.

The speed he wanted to move—the pace of iteration and experimentation that AI development demands—wasn’t just unsupported at Google. It was blocked by it. The processes, the review cycles, the organizational inertia. All the things that made Google successful at managing a search advertising business at massive scale were hindering someone trying to push the boundaries of what was possible with AI.

That’s not “I found a better opportunity.” That’s “staying was making me worse at what I do.”

When your best engineers don’t just leave—when they leave because your organization is actively holding them back—you’ve got a problem that can’t be solved with more funding or better marketing.

Why the Best Minds Leave

When you lose technology leadership, a secondary effect kicks in that’s harder to reverse than market share: your internal team becomes less capable over time. The best engineers want to work where the cutting edge is being pushed. Where the hard problems are being solved. Where their peers are doing exciting work.

Microsoft in the 2010s experienced this. Google might be starting to. When your flagship AI showcase features broken demos of concepts that others have already shipped, that sends a signal. Not just to customers. To your own engineers.

Android Authority noted the complete role reversal in 2023: “Microsoft is somehow delivering exciting new products that people are talking about, while Google is lagging behind.” But it’s worse than lagging. It’s about where the intellectual energy is flowing.

I was building more advanced agentic systems in the audience than they were showing on stage. Using their competitors’ tools. That shouldn’t be possible if they’re still the technology leader.

And that staff engineer who left? He’s shipping now. Fast. Building the kind of agentic systems that Google should be showcasing but isn’t.

The Real Comparison

Everyone’s debating whether Google is having a “Kodak moment”—inventing the technology but suppressing it to protect revenue, just as Kodak invented digital cameras but suppressed them to protect film. Multiple analysts have applied Clayton Christensen’s “Innovator’s Dilemma” explicitly to Google’s situation.

That’s part of it. But Microsoft 2010 faced an existential threat they couldn’t hedge against or outspend. Mobile was replacing desktop, and they had no position.

Google 2025 has hedged (the Anthropic investment), still dominates their core market (search), and has distribution advantages Microsoft never had (Chrome, Android, YouTube, Gmail). Recent research shows 99% of AI platform users still use traditional search engines—ChatGPT complements rather than replaces Google Search.

The threat isn’t as immediate. The financial position is stronger. The structural advantages are real.

But watching that presentation last week, I saw a substantive risk. Not strategic paralysis. Not protecting legacy revenue. Something more fundamental: they’re presenting mostly conceptual demos while developers are building real things elsewhere. And their own engineers are leaving because the company itself has become an impediment to the work they want to do.

When your showcase of advanced technology can’t match what a consultant is building in your audience with your competitors’ tools, you’ve got a developer mindshare problem. When your staff engineers leave because working there is slowing them down, you’ve got a talent retention challenge. And in tech, those are the leading indicators that eventually become market share issues.

The risk to Google isn’t that Pichai is the new Ballmer. He’s not. It’s that developer mindshare—including among their own engineers—is shifting to where the real agentic work is happening. Success breeds its own type of malaise, and that may be the most insidious threat of all.

I’m Bob Matsuoka, writing about agentic coding and AI-powered development at HyperDev. For more on multi-agent development, read my analysis of why I hope never to use Claude Code again or my deep dive into real-world orchestration results.